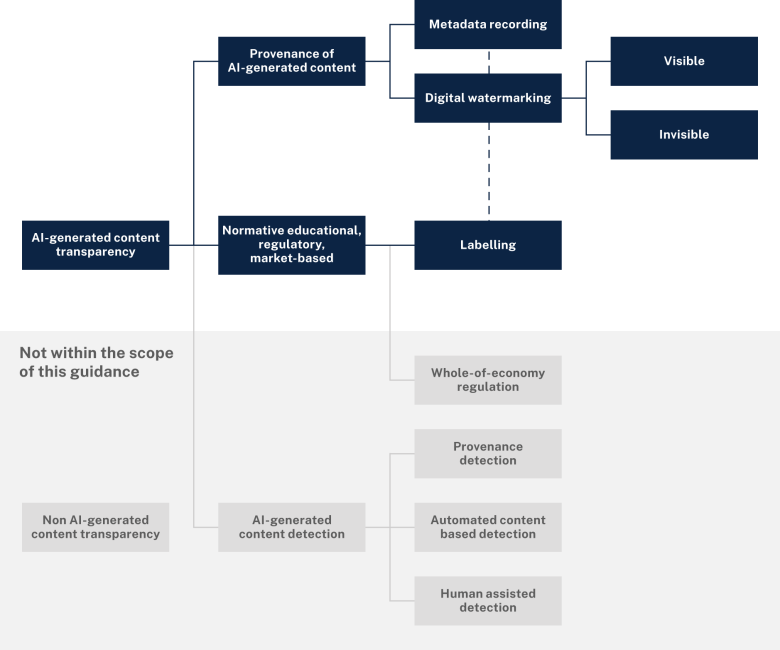

Watermarking and labelling – or using transparency mechanisms, as we’ve referred to it in this guidance – is an emerging field of AI governance. Relevant global industry‑led approaches such as open‑source internet protocol (C2PA) and information security controls (ISO 27002) continue to emerge. In November 2024, in the United States, the National Institute of Standards and Technology released its first synthetic content guidance report. This looked at the existing standards, tools, methods, practices and potential for development of further ways to deliver digital content transparency. In April 2024, the EU introduced mandatory regulatory requirements for providers of general‑purpose AI systems. These require providers to ensure their output is ‘marked in a machine‑readable format and detectable as artificially generated or manipulated’.

Widespread adoption of digital content transparency measures will be important to achieve broader economic and societal benefits as well as improve digital literacy. A coordinated approach can incentivise larger model developers to incorporate effective tools. It can also encourage sharing and collaboration on best practices, process and technologies.

The International Network of AI Safety Institutes has identified managing the risks from synthetic content as a critical research priority that needs urgent international cooperation. Australia is co‑leading the development of a research agenda focused on understanding and mitigating the risks from synthetic content, including watermarking and labelling efforts. The network aims to incentivise research and funding from its members and the wider research community, and encourage technical alignment on AI safety science.

Fostering greater transparency of AI‑generated content requires global collaboration across sectors and jurisdictions to create integrated and trusted systems that promote digital content transparency.

Limitations of transparency mechanisms

Approaches to digital content transparency continue to develop in industry and academia. While the benefits of being transparent about AI‑generated content are clear, some limitations remain:

- A lack of standardisation in watermarking technologies means that one watermarking system is not interoperable with another system.

- A lack of standardisation in approach across the economy can be a barrier to behaviour change. For example, a range of different content notifications may confuse the public. Or, in the case of widespread voluntary content labelling, users may assume that the absence of a label indicates that content is human‑generated. Measures to determine authenticity of human‑generated content are out of scope for this guidance, but are closely related.

- Watermarking and labelling techniques are vulnerable to being used maliciously and manipulated or removed, undermining trust in the system. As a result, we should also be pursuing tools of provenance to assist with more persistent trust capabilities in AI content.

It is also critical that systems that display or sell AI‑generated content (for example, social media platforms or retailers) make transparency mechanisms and information visible.

Further work across government

This voluntary guidance gives Australian businesses access to up‑to‑date best practice approaches to AI‑generated content transparency. These are based on the latest research and international governance trends – both of which are rapidly evolving. This guidance complements and recognises other Australian Government initiatives which impact AI‑generated content transparency including:

Under Australia’s Online Safety Act 2021, the eSafety Commissioner regulates mandatory industry codes and standards. These set out online safety compliance measures to address certain systemic online harms. There are a range of enforcement mechanisms for services that do not comply, including civil penalties. Watermarking, labelling or equivalent measures are part of the Online Safety (Designated Internet Services – Class 1A and Class 1B Material) Industry Standard 2024 (DIS Standard). This requires that certain generative AI service providers – those with a risk of being used to produce high impact material like child sexual abuse material – put into place systems, processes and technologies that differentiate AI outputs generated by the model, as well as other obligations. The Internet Search Engine Services Online Safety Code (Class 1A and Class 1B Material) requires search engine providers to make it clear when users are interacting with AI‑generated materials, among other obligations.