Principle 3: New sources of gas supply are needed to meet demand during the economy-wide transition. Government policies to enable natural gas exploration and development should focus on optimising existing discoveries and infrastructure in producing basins, applying technology-neutral approaches to exploration data acquisition (to minimise seismic surveying where possible), prioritise energy security, and align with our net zero emissions targets. Robust environmental approval processes are key to the social license of the gas industry.

Summary

Gas remains crucial to our economy and region to support the transition to net zero. To meet our future energy needs and decarbonise our economy, we need continued gas supply:

- at the right time

- in the right place

- with high levels of workplace safety and conditions

- at the lowest cost

- at the lowest emissions intensity

- with the least impact on our environment

- with the maximum benefit for communities.

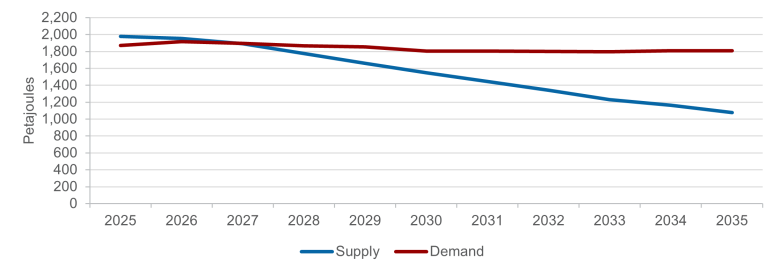

In the near term, there is concern around the potential for demand to outstrip supply over coming years. This annual supply gap is forecast to emerge in 2028 on the east coast and by 2030 on the west coast if there is insufficient new supply developed. Meeting these supply challenges will need location-specific solutions, including:

- maximising production from existing resources and developing adjacent new gas fields supplying the domestic market, provided environmental impacts can be managed

- demand reduction through the net zero sectoral plans

- gas substitution through expanding the supply of low emission gases

- LNG producers making more gas available to domestic users

- expanding gas infrastructure, including pipelines and LNG import terminals.

We will likely need to explore all of these solutions to meet our gas demand needs through to 2050.

Developing new gas supply is technically challenging, expensive, and a lengthy process. Gas fields deplete as gas is extracted. Exploring for gas requires advanced technology and techniques, such as seismic surveys which, as with any other human activity, have the potential for some level of impact on the environment and must be managed accordingly. We need new and continued investment to develop and sustain supply to meet demand. This investment is facilitated by a strong regulatory framework that aims to balance environmental and social impacts while encouraging new supply. There is always room to improve our regulatory settings. They must remain fit for purpose to achieve Australia’s goals.

Without continued investment in Australia’s gas sector, both the east and west coast markets could experience gas price and supply volatility. In the near term, potential shortfalls in gas supply could increase volatility in gas markets and drive up prices. Without further investment in new gas supply and gas infrastructure, these shortfalls will negatively affect Australian households and businesses, and the reliability of our electricity system.

Alternative gas sources may also meet demands for gas. Low-emission gases such as hydrogen and biomethane may become important elements of Australia’s energy landscape, as well as adding to our exports. These low-emissions gases are not yet produced at a scale or price able to compete with natural gas. However, they are expected to become more competitive as technology costs reduce and these gases are produced on a commercial scale.

Read Appendix A for more information about the scenarios that are used to help shape forecasts in this section.

Read Section 2 of the analytical report for information about alternative clean fuels, Section 5 of the analytical report for the natural gas supply outlook, and Section 7 for analysis of options to close the supply gap.

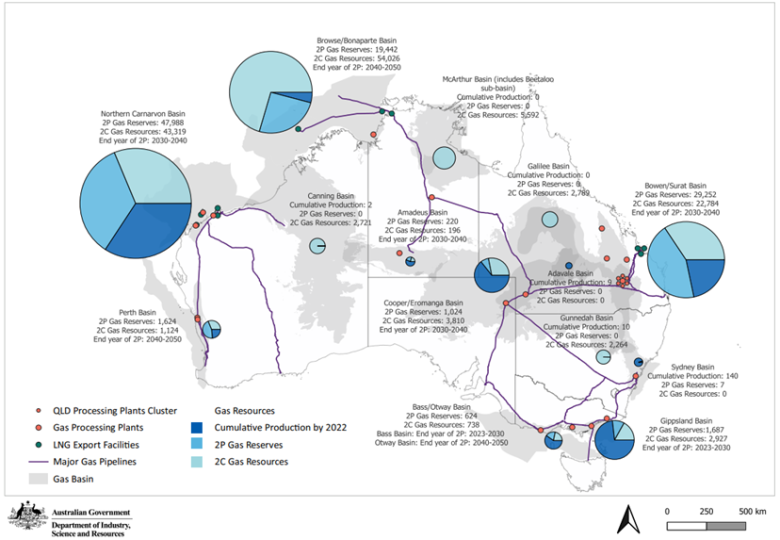

Where is natural gas produced today?

While Australia has substantial gas resources, they are not evenly spread. Most of Australia’s remaining gas reserves are offshore, in the Northwest Shelf region, onshore Queensland, and onshore and offshore Northern Territory. This places most of the Australian gas resources and reserves geographically far from demand centres in the southern states. Gas produced in Commonwealth waters, south of Victoria, has declined to low levels after 50 years of production. This offshore resource in Commonwealth waters is processed in Victoria, and supplied to customers in Victoria, Tasmania, NSW and South Australia.

The Australian Capital Territory does not produce gas. New South Wales, which currently produces minor quantities of natural gas, plans to develop resources around Narrabri in the Gunnedah Basin. If developed, Narrabri is expected to produce around 70 PJ per year for the domestic market once fully operational.

This production does not precisely align with gas markets. Australia has three distinct market segments with materially different outlooks for gas.

- East coast gas market has two segments:

- southern states comprised of NSW, ACT, Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania

- northern states of Queensland and the Northern Territory.

- Western Australia is physically separated from the east coast gas market.

With local production in the Bass Strait approaching end of life, the southern states face the prospect of becoming dependent on gas transported from northern gas fields, or on yet-to-be-completed LNG import terminals to meet domestic demand. However, as noted previously, LNG imports to the east coast may be more expensive than the nearby depleted sources in offshore Commonwealth waters near Victoria.

Responsible management of Australia’s natural gas resource is critical for securing the stable and affordable energy supply needed for economic growth while aligning with Australia's emissions reduction targets. Without future investment, there are real risks gas will become unaffordable and unavailable to Australian households and industry well before 2050. Accordingly, further exploration, acreage release and gas production will be required.