Australia’s talent pool is limited by the underrepresentation of half of Australia’s population – girls and women – in STEM education and careers. The causes of poor attraction and retention of girls and women in STEM begin from an early age and compound as progression to more senior careers is made. Often referred to as a ‘leaky pipeline’, the result is a system with low representation of women in STEM education, workplaces, and senior level leaders, and a society that undervalues the opportunities and contributions a career in STEM can provide for girls and women. Differing participation rates in STEM education and fields also means that gender inequities can transpire at different points of the career path depending on the individual field.

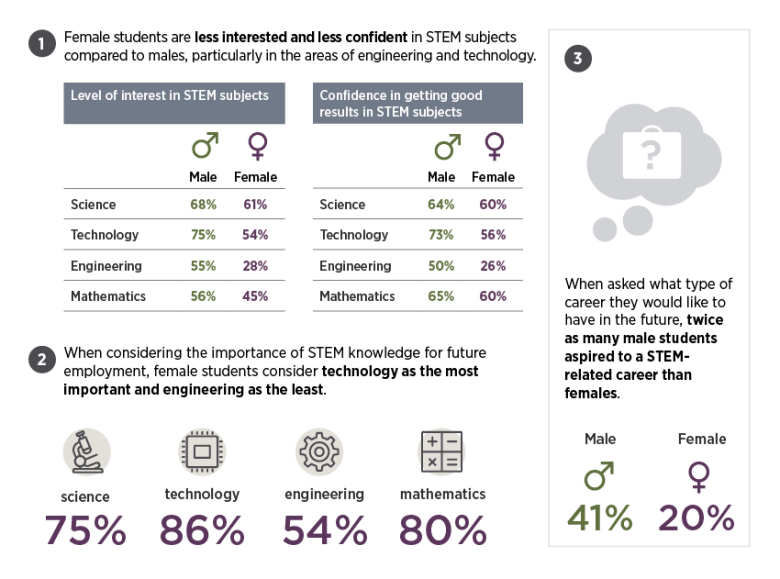

At the school-level, despite boys and girls having similar average performance in the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), in 2017 fewer girls achieved at the highest levels in NAPLAN year 3 and 5 numeracy tests compared to boys.[7] By year 12, there are marked participation differences in a number of STEM subjects. For example, while girls comprise over 50 per cent of enrolments in year 12 Sciences subjects, they are underrepresented in Information and Communication Technology and Design and Technology subjects with only 26.3 per cent of year 12 girls enrolling in 2017 compared to 39.4 per cent of year 12 boys.[8] In year 12, boys outnumber girls 3 to 1 in physics and almost 2 to 1 in advanced mathematics.[9] Low participation in these critical subjects directly impacts future opportunities for girls, whether in a STEM career or not, and is a major contributor to the gender imbalance in STEM tertiary education and the STEM workforce.

At the tertiary level, both at universities and in vocational education and training (VET), underrepresentation in information technology (IT) and engineering education is of particular significance, especially as these skills will be increasingly important as Australia transitions to a digital and technologically-driven economy. In 2016, women comprised less than 15 per cent of domestic Engineering and Related Technologies undergraduate course completions[10],[11] and less than 11 per cent of vocational education course completions.

While participation rates in other broad fields of tertiary STEM education such as the Natural and Physical Sciences may not present cause for concern at the surface level, deeper examination also shows underrepresentation of women in more specific fields of education such as Mathematical Sciences (37 per cent of domestic undergraduate and postgraduate completions in 2016) and Physics and Astronomy (29 per cent of domestic undergraduate and postgraduate completions in 2016).[12] Comparison of enrolment and completion data indicates most women who enter into these fields of education complete their courses, suggesting issues other than attrition are of importance during this stage of the career.[13]

Consistent low levels of participation in STEM education means the number of women participating in the STEM workforce is not increasing at a substantial rate. Of the STEM qualified population, women comprised only 17 per cent in 2016.[14] In academia, participation at junior levels is not an issue for all STEM fields, however women are still poorly represented as a total of STEM academics (31 per cent in 2016).[15] Representation of women at senior levels (14.5 per cent in 2016) is extremely poor, even for traditionally female dominated fields such as biology – in 2016, women comprised 56 per cent of postdoctoral biology academics, but only 18 per cent of professors.[16] These issues are not specific to academia and cut across much of the STEM workforce. In engineering, women represented only 12.4 per cent of the workforce in 2016, with men more likely to be employed at higher levels of responsibility and women at less senior levels.[17],[18] In IT, women are also poorly represented in higher positions and made up only 28 per cent of the workforce in 2017, a figure that has remained unchanged since 2015.[19] This trend of workforce distribution, with the compounding factors of low participation rates, more women working at lower levels than in senior positions and high levels of midcareer attrition due to these factors, also results in a gender pay gap for STEM. This ranges from 11 per cent in engineering and 12.4 per cent in science, to 20.2 per cent in IT.[20]

What is causing this disparity?

Issues of women’s participation are not exclusive to STEM fields. In the Australian workforce, women have lower work participation rates than men and also earn less than men, with the weekly pay gap currently at 14.2 per cent (average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time employees).[21] Women’s participation is lower for a variety of reasons, from cultural barriers in the workplace through to women being more likely to be a primary carer for children or other family members. As at January 2019, there is a 9.3 percentage point difference between men (83.0 per cent) and women (73.6 per cent) labour force participation for persons aged 15 to 64 years.[22]

Girls and women, especially those from minority groups, rural and remote areas and disadvantaged backgrounds, face multiple barriers to STEM participation and as a result have to overcome more challenges than their male counterparts.[23],[24] Factors such as bias and stereotyping, career insecurity, a lack of flexible work arrangements, and lack of female role models have been demonstrated to greatly influence girls and women’s decisions to enter and remain in STEM education and careers.[25],[26]

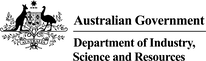

Experiences of bias and stereotyping begin early in life and have a significant impact on girls and women’s development of confidence and interest in STEM.[27],[28] The perception that some STEM fields are a better fit for males, particularly by influencers such as parents, educators, and career counsellors, is one of the biggest barriers to girls and women participating and persisting in STEM.[29]

A lack of diverse female role models in STEM, whether in the classroom, at work or on the screen, further decreases girls’ and women’s likelihood of persisting in STEM education and considering STEM as a career option. For girls, female role models are crucial to their perception of whether they could work in STEM.[30] In fields where women are particularly underrepresented such as physics and engineering, surveys have found more than 80 per cent of women perceive a lack of female role models as a significant hurdle for gender equity in their field.[31]

Working conditions and job insecurity have a strong negative impact on women entering into and maintaining careers in STEM, and are longstanding issues. STEM employees encounter less flexible working conditions, large numbers of short-term contracts, grant dependent positions, and pathways to promotions that can be subject to gender bias. Particularly in academia, finding ongoing positions (tenure) can be very difficult. Additionally, the pathway to senior positions in STEM academia and industry has traditionally been seen as one where there are no career breaks or access to part-time duties, with STEM professionals reporting that taking maternity leave is detrimental to their careers.[32]

In many STEM fields, maintaining skill sets and professional networks are vital to career progression, however gendered caring expectations and different work place approaches to facilitating part-time work make opportunities to undertake training to re-learn, maintain or gain new skills and attendance at networking events or conferences difficult. A further lack of support networks, including mentors, career sponsors and professional groups, contributes to women feeling out of place in STEM fields, and can lead to thoughts about leaving the field.[33] Feeling like a misfit, or an imposter, hinders achievement, engagement, and persistence in STEM education and careers, and causes girls and women to question their abilities and interest in STEM.[34]

Understanding the STEM journey for women

A women’s journey through STEM can be impacted by many factors. The following infographic represents where known pressures and key influencers (who can help or hinder progression) first appear, noting many of these continue throughout the education and career path once they are present and may be experienced differently by individuals.